The following is the full excerpt of Christopher Staker for the defense of Myanmar against The Gambia's accusations of genocide at The International Court of Justice, The Hague, Netherlands on December 11 2019.

LACK OF PRIMA FACIE JURISDICTION OF THE COURT; LACK OF PRIMA FACIE STANDING OF THE GAMBIA; INAPPROPRIATENESS OF THE PROVISIONAL MEASURES REQUESTED

1. Mr. President, Members of the Court, it is an honour to appear before you again, now on behalf of Myanmar.

2. I will address you on two of the prerequisites for provisional measures: prima facie jurisdiction, and prima facie standing. Factual background relevant to prima facie jurisdiction and prima facie standing.

3. But I begin with some background facts, pertinent to both issues, taken from publicly available documents contained in the Judges’ folder, under section 3, tabs 3.1 to tab 3.17.

4. The documents I will take you to show the following. Although The Gambia is the nominal Applicant, these proceedings are in fact brought on behalf of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, the “OIC”. The Gambia has been tasked by the OIC to bring them, acting in its capacity as an OIC Member State and chair of an OIC organ, its ad hoc committee. Moreover, the proceedings are financed by a fund supervised by the OIC. While the OIC decided to bring this case as early as March this year, the earliest official reference we can find to the Genocide Convention as the basis of the claim is in August. And the Applicant’s lawyers were instructed to initiate proceedings a week before The Gambia even sent its 11 October Note Verbale to Myanmar.

5. Time constraints require me to take you through these documents quickly, and I am confident that they will be given all due consideration. I will refer to tabs: within a tab, the French version, if available, follows the English version.

6. At tab 3.1 74 is a May 2018 OIC resolution establishing an ad hoc Ministerial Committee on Accountability for human rights violations against the Rohingya, to be chaired by The Gambia. The Committee’s functions include to “[e]ngage to ensure accountability and justice for gross violations of international human rights and humanitarian laws and principles”, and to “[m]obilize and coordinate international political support”. A preambular paragraph states that “ensuring accountability and justice is the most crucial step towards preventing genocide and other mass atrocity crimes”. It does not say that genocide has actually been committed. In fact, the very opposite is implied when this statement is contrasted with the previous preambular paragraph, expressing concern that “the Rohingyas taking shelter in Bangladesh had been victims of gross and systematic violations of human rights and atrocity crimes”, and an earlier preambular paragraph that refers to “ethnic cleansing and forced expulsions”80.

7. That same session of the OIC Council of Foreign Ministers in May 2018 saw the adoption of the “Dhaka Declaration”, which was referred to in the argument of The Gambia yesterday, found at tab 3.2. This document does not contain the word genocide. It does refer to “ethniccleansing” and to State-backed violence. The Government of Myanmar issued a press release after that, found at tab 3.3, which affirmed that no violations of human rights would be condoned, that allegations supported by evidence would be investigated and action taken in accordance with the law, and that there was an immediate need for repatriation of displaced persons from Rakhine in accordance with the bilateral MOU between Myanmar and Bangladesh.

8. On 25 September 2018, the President of The Gambia made a statement in the General Assembly, relied on in oral argument yesterday, in which he referred to “terrible crimes against the Rohingya Muslims”, but made no mention of the Genocide Convention, or of genocide at all.

9. At tab 3.4 is an OIC resolution from March this year, virtually identical to the one at tab 3.1, with the same preambular paragraphs. Then at tab 3.5 is another resolution adopted at the same session, in which Member States decide to “[e]ndorse the Ad Hoc Committee’s plan of action to engage in international legal measures to fulfill the Ad Hoc Committee’s mandate”, and to “[c]all upon member states to contribute voluntarily to the budget of the plan of action”. Contrary to what was suggested in oral argument yesterday, this resolution contains no specific reference to the International Court of Justice, but a media article, at tab 3.689, states that at this OIC session there was a “major diplomatic breakthrough” in that a resolution was adopted “to move the International Court of Justice (ICJ) for establishing the legal rights of Rohingya Muslims”. According to this report, the Bangladesh Foreign Ministry announced that the resolution to pursue a case in this Court “came after a long series of negotiations”.

10. An official press release at tab 3.7 then states that on 30 May, the Bangladesh Foreign Minister appreciated the “Gambia led initiative of taking legal recourse to establish Rohingya rights and address their justice question at the International Court of Justice against Myanmar”. There is no mention of the legal basis of the claim.

11. At tab 3.890 is the 31 May Final Communiqué of the 14th Islamic Summit Conference, affirming support for using all international legal instruments to hold accountable the perpetrators of crimes against the Rohingya, and urging the ad hoc Ministerial Committee to launch the case at the International Court of Justice on behalf of the OIC. Still no mention of the legal basis.

12. This Final Communiqué is referred to in an undated item on the website of the Office of the President of The Gambia, at tab 3.991, except that the second paragraph of this page mistakenly refers to the International Criminal Court rather than the International Court of Justice. The Office of the President of The Gambia was possibly not clear on the details of this proposed court case.

13. Tab 3.1092 is a 6 July media article, indicating that the OIC then formally proposed that The Gambia lead proceedings in this Court, and that the Cabinet of The Gambia then approved that proposal.

14. Paragraph 107 of the 8 August Fact-Finding Mission Report, tab 3.1193, then refers to “the efforts of States, in particular Bangladesh and the Gambia, and the . . . [OIC] to encourage and pursue a case against Myanmar before the International Court of Justice under the [Genocide Convention]”. This is the earliest official document we are aware of referring to the Genocide Convention as the proposed basis of the claim. The absence of any earlier mention is striking. In oral argument yesterday, The Gambia relied on a press report stating that a decision to base the claim on the Genocide Convention had been taken in March, but did not refer to any official document prior to August stating that.

15. The document at tab 3.1295 then says as follows. These proceedings are funded by voluntary donations from OIC Member States. Supervision of the funds is entrusted to the Chair of the ad hoc Ministerial Committee and the OIC Secretary General. Assistance has also been requested from the Islamic Development Bank and the Islamic Solidarity Fund.

16. At tab 3.1399 is a 26 September statement in the General Assembly by The Gambia’s Vice-President that these proceedings involve “concerted efforts . . . ‘on behalf of the [OIC]’”.

17. Two weeks later, on 11 October, The Gambia sent to Myanmar the Note Verbale seen at Annexes 1 and 2 of the Observations of The Gambia.

18. Tab 3.14101 is an internet article reporting a statement of The Gambia’s Attorney General, now its Agent, that lawyers were instructed to bring these proceedings on 4 October. Thus, the instruction to issue these proceedings had in fact already been given to the Applicant’s lawyers a week before the first Note Verbale was even sent to and received by Myanmar.

19. Tab 3.15102 is an 11 November item on the website of the law firm representing The Gambia, confirming that “[t]he OIC appointed The Gambia, an OIC member, to bring the case on its behalf”.

20. Tab 3.16104 is an article from the Jakarta Post on 19 November, an example of media confirming that this case is brought on behalf of the OIC.

21. At tab 3.17105 the OIC confirms on 24 November that these proceedings have indeed been brought by “the Republic of The Gambia, as Chair of the OIC Ad Hoc Ministerial Committee”, and that The Gambia has been “tasked with submitting the case to the ICJ, following a decision by the OIC Heads of State”.

22. I note that, on 12 November, after this case had already been introduced, Myanmar sent the Note Verbale found at Annexes 3 and 4 of the Observations of The Gambia, to which The Gambia’s response is at Annexes 5 and 6 of The Gambia’s Observations Lack of prima facie jurisdiction of the Court: acting on behalf of an international organization

23. Mr. President, Members of the Court, it is unprecedented for a State to invoke the Court’s contentious jurisdiction as the proxy for an international organization. The actual seisin of the Court was performed by The Gambia as chair of the OIC Ad Hoc Ministerial Committee, as an organ of the OIC, not in its capacity as a contracting party to the Genocide Convention.

24. While The Gambia is said to be “leading” this OIC initiative, it is unknown who else is controlling it. It is unknown which States have donated what to the voluntary fund, or whether the donors are even confined to States.

25. This is a circumvention of the limitations of Article 34 of the Statute: only States may be parties in cases before the Court. An international organization without even a mandate to seek an advisory opinion from the Court is seeking to circumvent that restriction by nominating a State to act as its substitute and bring a contentious case. If permissible, this would allow “the restrictions on personal jurisdiction which are matters of public policy, to be evaded, virtually at will, simply by nominating a mandatory”109. Furthermore, Myanmar’s consent to the Court’s jurisdiction is valid only vis-à-vis another State accepting the same obligation; it must be inapplicable where the substantive applicant is an inter-governmental organization with no standing before the Court.

26. Indeed, of the OIC’s Member States110, 13 are not even parties to the Genocide Convention, while seven including most importantly Bangladesh have made reservations to its Article IX that prevent them from bringing proceedings against Myanmar under Article IX of that Convention113. For this reason alone jurisdiction is lacking.

Lack of prima facie jurisdiction of the Court: absence of a dispute

27. Mr. President, Members of the Court, a further requirement that is essential for the exercise of the Court’s contentious jurisdiction is the existence of a dispute. This is also expressly required by Article IX of the Genocide Convention115 which provides only for the submission to this Court of disputes between contracting States. In the absence of a dispute, Article IX of the Genocide Convention simply does not apply.

28. The erga omnes partes character of obligations under the Genocide Convention does not mean that The Gambia can bring these proceedings in the absence of a dispute specifically between the two Parties now before the Court. In Belgium v. Senegal, while the Court accepted that the erga omnes partes character of a treaty obligation might be of some relevance to standing, the Court’s consideration of jurisdiction proceeded on the obvious premise that there had to be a dispute between Belgium and Senegal for there to be jurisdiction under the Convention against Torture.

29. As Article IX of the Genocide Convention is the only basis of jurisdiction, the only dispute over which this Court could potentially have jurisdiction is one concerning obligations arising specifically under that Convention. The Court has no potential jurisdiction over disputes concerning customary international law obligations regarding genocide119, or disputes concerning alleged breaches of other treaty or customary international law obligations, even if those alleged breaches are of obligations under peremptory norms, or of obligations which protect essential humanitarian values, and which may be owed erga omnes.

30. For the Court to have jurisdiction, there must accordingly be first, a dispute, which secondly is specifically between The Gambia and Myanmar, and which thirdly, concerns specifically the interpretation, application or fulfilment of the Genocide Convention.

31. Beginning with the second of these requirements, there is no dispute between The Gambia and Myanmar because these proceedings are in fact brought on behalf of and funded by the OIC. We see that the Applicant delegation here in court includes several high ranking officials of the OIC. If any dispute has been brought before the Court, it is the OIC’s, not The Gambia’s.

32. But even aside from that, there is no dispute at all.

33. According to the established case law, the existence of a dispute is determined as at the date on which the application is submitted to the Court. The allegations contained in The Gambia’s Application, and the arguments within these proceedings, cannot generate a dispute de novo if one did not already exist at the date of Application. For a dispute to exist, “it must be shown that the claim of one party is positively opposed by the other”, and that “the two sides hold clearly opposite views concerning the question of the performance or non-performance of certain international obligations”.

34. The Gambia relies on several matters to establish the existence of a dispute.

35. First, The Gambia relies on various OIC documents125. These clearly do not give rise to a relevant dispute between The Gambia and Myanmar. They contain no positive statement that Myanmar is in breach of its obligations under the Genocide Convention. Indeed, as I have explained, the preamble to two OIC resolutions implies the opposite. In any event, this Court has affirmed that a State’s vote on a resolution of an international organization is not of itself indicative of that State’s position on each proposition within the resolution, let alone of the existence of a legal dispute with another State regarding one of those propositions. Furthermore, Myanmar is not a member of the OIC and there is nothing to indicate that Myanmar was put on notice of all of its resolutions.

36. Secondly, The Gambia relies on reports of the Fact-Finding Mission127. However, statements in reports of the Fact-Finding Mission do not constitute claims by The Gambia or the OIC or its Member States. Statements by the Fact-Finding Mission do not put Myanmar on notice of what particular claims those States and the OIC might be intending to make in Court proceedings.

37. Thirdly, the general statement by the Vice-President of The Gambia that The Gambia is “ready to lead concerted efforts” to bring this case128 does not even mention the Genocide Convention.

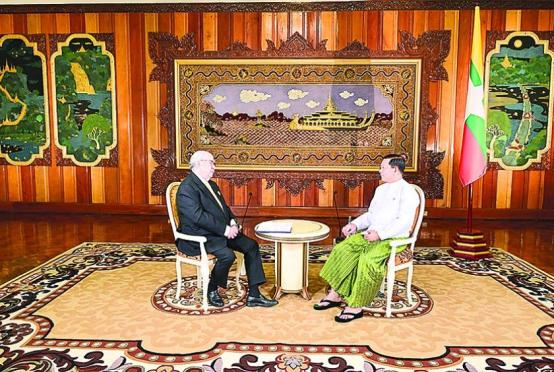

38. Similarly, the statement by Myanmar’s Union Minister for the Office of the State Counsellor does not mention the Genocide Convention.

39. In short, these documents do not amount to allegations against Myanmar of violations of the Genocide Convention, and are not otherwise sufficient to found a justiciable dispute between the Parties.

40. There is then the 11 October Note Verbale131. The Gambia’s case is that because Myanmar failed to respond to it within a month, by 11 November a dispute between the Parties concerning the matters set out in that document had suddenly arisen.

41. However, the existence of a dispute can be inferred from a failure to respond to a claim only in circumstances where a response is called for, and where an acceptable time for any response has expired.

42. This Note Verbale did not call for a response. It contained only a sweepingly general claim that Myanmar had “responsibility for the ongoing genocide against Myanmar’s Rohingya population”. It contained no particulars. It does not specify which particular facts are relied on in support of the assertion of that responsibility. It does not specify which provisions of the Convention are claimed to have been violated by which facts. It provides no particulars of the facts that are alleged to constitute “Myanmar’s refusal to acknowledge and remedy its responsibility”. It refers only in the most general way to the reports and findings of the Fact-Finding Mission and to OIC resolutions (but specifies only one of each), and generically to obligations under the Genocide Convention, customary international law and human rights covenants. It does not make any particular legal or factual claim that could be positively opposed by Myanmar. It merely states a legal conclusion — that there is an ongoing genocide for which Myanmar is responsible — without stating any claim that is said to justify that conclusion.

43. It cannot be sufficient, for there to be a “dispute” under Article IX of the Genocide Convention, that the Applicant has referred the Respondent to a report of an international organization, or an NGO, or anyone else, suggesting that the latter is in breach of its obligations under that Convention, and that the latter has not responded.

44. A failure to respond to the Note Verbale therefore could not give rise to a dispute. However, even if it could, it cannot possibly be argued that the response was called for in the space of a single month, given that the detailed findings of the Fact-Finding Mission are some 180 pages long, and the Note Verbale contains no more than an unparticularized conclusion. Furthermore, as the Agent of Myanmar observed earlier this morning, allegations of the most serious crimes need to be considered and determined in the course of the criminal justice process. These are not matters on which political representatives of countries can be required to take firm positions in short spaces of time and even less so where the State making such a claim does not provide any timeline for any such response in the first place.

45. The second Gambian Note Verbale of 24 November134 adds nothing. It was sent after this case had already been brought, and cannot ex post facto bring about a relevant dispute. In any event, it does nothing further to identify a legal claim.

46. Furthermore, the OIC, on whose behalf the proceedings are brought, has never directly accused Myanmar of violations of the Genocide Convention. Rather, the OIC has expressed support more generally for “using all international legal instruments to hold accountable the perpetrators of crimes”. These proceedings are the initiative of an OIC subcommittee whose task is generally to “[e]ngage to ensure accountability and justice for gross violations of international human rights and humanitarian laws and principles”. The impression is that the OIC wanted to bring “a” case before the Court, but was not particularly concerned with the legal basis of the claim, that Article IX of the Genocide Convention was simply identified at some point by someone as a vehicle for invoking the Court’s jurisdiction, and that the OIC would have been equally prepared to use any other treaty it could identify for that purpose.

47. If The Gambia had a genuine dispute with Myanmar concerning the interpretation, application or fulfilment of the Genocide Convention, why did it not give notice of this claim to Myanmar in March, when a decision to bring these proceedings was made or in August when the 2019 Fact-Finding Mission report noted that it was intended to bring a claim based on the Genocide Convention? Why did it not give notice of this claim to Myanmar before instructing lawyers on 4 October to institute proceedings? The inference is that the Note Verbale was sent as a legal formality, considered necessary to enable proceedings to be issued, once all preparations for the proceedings were already in place.

Mr. President, Members of the Court,

48. Myanmar’s position is that for all these reasons, the lack of jurisdiction is manifest, and that even at the provisional measures stage, it is clear that the proceedings should not continue further. The appropriate course would be to strike the case from the Court’s General List. As the Court said in two137 of the previous cases where it adopted such a course at this stage, it would most assuredly not contribute to the sound administration of justice to keep a case on the General List when it appears certain that the Court cannot adjudicate on the merits.

Lack of prima facie standing of The Gambia

Mr. President, Members of the Court,

49. I now turn to the issue of prima facie standing.

50. The Gambia says it has standing to bring the case, even though it is not specially affected by the subject-matter of the claim, because of the erga omnes and erga omnes partes character of obligations owed under the Genocide Convention.

51. At the outset, I note that erga omnes and erga omnes partes are not the same thing.

52. The term erga omnes refers to obligations under customary international law owed to the international community as a whole. Thus, in the Barcelona Traction Judgment, the Court referred to rights that had entered “into the body of general international law”, with corresponding obligations of States owed to “the international community as a whole” being labelled obligations erga omnes.

53. On the other hand, the term erga omnes partes refers to multilateral treaty obligations. Such obligations are owed only to the community of States parties to that particular treaty. As this Court said in Belgium v. Senegal, each State party has an interest in compliance with such obligations.

54. Myanmar accepts that at least some obligations under the Genocide Convention are erga omnes partes.

55. However, even if The Gambia has an interest in Myanmar’s compliance with erga omnes partes obligations under that Convention, it does not follow without more that The Gambia also has standing to bring a case before the Court in respect of a claimed breach by Myanmar, without being specially affected.

56. A State that is specially affected by the events the subject-matter of these proceedings is obviously Bangladesh. However, Bangladesh could not have instituted these proceedings without the consent of Myanmar because of a reservation that it has made to Article IX of the Genocide Convention.

In fact, none of Myanmar’s neighbours, with the exception of Laos. could have done so, since each of the others is either not a party to the Genocide Convention146 or has made a reservation that Article IX applies either not at all, or only with the consent of all parties to the dispute. If a State such as The Gambia that is not specially affected by an alleged breach of a treaty could bring a case, in circumstances where a State that is specially affected cannot, this would represent a major inroad into fundamental principles concerning the consensual nature of this Court’s jurisdiction.

57. Indeed, the implications are far wider than this. If a State not specially affected can seek enforcement of erga omnes partes obligations by bringing a claim in this Court, there would be no reason why it could not seek enforcement of those obligations by other means permitted under international law, such as by taking countermeasures. Yet, in the course of its work on its draft Articles on State Responsibility, the International Law Commission (ILC) noted, in the context of countermeasures, that “even accepting the proposition, on the basis of the Barcelona Traction case, that States at large had a legal interest in respect of violations of certain obligations, it did not necessarily follow that all States could vindicate those interests in the same way as directly injured States”. A subsequent 2001 report by the then special rapporteur observed, in relation to the then draft Article providing that any State could take countermeasures in cases of an internationally wrongful act that constitutes a serious breach by a State of an obligation owed to the international community as a whole and essential for the protection of its fundamental interests that “[t]he thrust of Government comments is that [the provision], has no basis in international law and would be destabilizing”.

58. In Barcelona Traction the Court did not address this specific question of standing because the case as such was not concerned with obligations erga omnes and even less with obligations erga omnes partes. It was only Judge Ammoun who did expressly accept the right of any State to enforce obligations erga omnes by way of bringing a case before the Court, making the omission of any other judge or the Judgment itself to do so significant.

59. Moreover, in all other cases brought before the Court involving the Genocide Convention, the Applicant was a specially affected State and thus the proceedings did not involve any kind of actio popularis.

60. In the Bosnia Genocide case, Judge Oda in fact expressed the view that while legal obligations arising under the Genocide Convention are “borne in a general manner erga omnes by the Contracting Parties”, a failure to comply with such obligations cannot be rectified by an inter-State dispute before this Court, while the late Roberto Ago had previously taken the same view.

61. It is true that in Belgium v. Senegal, the Court held that Belgium had standing as a State party to the Convention against Torture to bring a case against Senegal for alleged breaches of that Convention. The Court therefore declined to pronounce on whether Belgium also had a special interest with respect to Senegal’s compliance. However, I would emphasize:

62. First, this one case does not amount to established jurisprudence of the Court, and Judge Skotnikov and Judge Xue disagreed with the Court’s decision on standing.

63. Secondly, Belgium itself did in fact claim to be an “injured State” under Article 42 (b) (i) of the ILC Articles on State Responsibility.

64. And thirdly, Belgium was indeed affected by the outcome of that case. The Convention against Torture contained an aut dedere aut judicare obligation, and Belgium had availed itself of the specific right under Article 5 to exercise jurisdiction and to request extradition. This case was thus not a genuine actio popularis, brought by a State that was individually completely unaffected by the subject-matter of the claim. In contrast, the Genocide Convention contains no aut dedere aut judicare obligation, and indeed, Myanmar has made a reservation to Article VI of the Genocide Convention that prevents the courts of any other State from exercising jurisdiction over genocide allegedly committed in its territory.

65. Ultimately, no decided case is precedent for standing for a pure actio popularis of this kind. While every State to whom an erga omnes partes obligation is owed may have an interest in compliance with that obligation, and may even be entitled to invoke the claimed breach in international relations, when it comes to standing to bring a claim before this Court, a balance has to be achieved. Allowing a pure actio popularis would open potential floodgates, to use a hackneyed but apt expression.

66. Normally, it is States most specially affected by international crises who are involved in diplomatic negotiations and practical initiatives to seek a resolution of the situation. It is those States who are best placed to judge when the bringing of a case before this Court would help or hinder those efforts. Allowing any State party to a major international treaty like the Genocide Convention, no matter how far removed from events they are, to bring a case such as this at any time of its own choosing against any other contracting party, could well prove counterproductive to such diplomatic negotiations and practical initiatives.

67. Furthermore, even if, contrary to my submissions, such an actio popularis was possible, this would not mean that the Court could order provisional measures in such a case. Under Article 41, paragraph 1, of the Statute, the Court only has power to indicate provisional measures “to preserve the respective rights of either party”.

68. There is also one further reason why The Gambia has no standing.

69. Myanmar has made a reservation to Article VIII of the Genocide Convention. As the Court is aware, Article VIII states that “[a]ny Contracting Party may call upon “saisir” in French — the competent organs of the United Nations to take such action under the Charter of the United Nations as they consider appropriate for the prevention and suppression of acts of genocide". However, Myanmar’s reservation means that Article VIII does not apply to it.

70. Article IX of the Convention, to which Myanmar has made no reservation, clearly confers jurisdiction on the Court in the circumstances described. However, this Court can only exercise jurisdiction if it is first validly seised of a case. Valid seisin of the Court “saisine de la Cour” thus constitutes a necessary condition precedent to the exercise of the Court’s contentious jurisdiction. We submit that Article VIII, as confirmed by its wording, deals with seisin. It permits any of the contracting parties of the Convention to seise any competent organ of the United Nations with any alleged situation of genocide, and to request it to take action under the Charter of the United Nations, of which the Court’s Statute forms an integral part. The reference in Article VIII to competent organs of the United Nations must include this Court,which, to state the obvious, is one of its principal organs. Even if the conclusion were to be reached that a genuine actio popularis is possible under the Genocide Convention, sed quod non, this would be the result of Article VIII rather than the result of Article IX. By contrast, Article IX does not refer to any dispute; it is confined to “disputes between the Contracting Parties in relation to the interpretation, application or fulfilment of the present Convention”. Nor does Article IX speak of any contracting party; it applies only to “the Contracting Parties” and “the parties to the dispute”. These linguistic differences make clear that Article IX has a narrower remit than Article VIII.

71. Thus, where, as here, the respondent State has made a valid reservation to Article VIII, the effect is that the Court cannot be seised of this case, even though there is no reservation to Article IX.

72. As this Court has said, “[t]he consent allowing for the Court to assume jurisdiction must be certain”; “whatever the basis of consent, the attitude of the respondent State must ‘be capable of being regarded as “an unequivocal indication” of the desire of that State to accept the Court’s jurisdiction in a “voluntary and indisputable” manner’”. On any view, it is evident from the fact of Myanmar’s reservation to Article VIII that it has not given any such unequivocal indication in an indisputable manner.

73. For all these reasons, Myanmar submits that The Gambia has no prima facie standing. Inappropriateness of the provisional measures requested.

74. Mr. President, Members of the Court, as a prelude to Ms Okowa’s observations, I will finally address you on the wording of the six provisional measures requested by The Gambia.

75. The first two provisional measures, requested by The Gambia in paragraph 132 (a) and (b) of the Application, are essentially the same as the first two orders that it seeks by way of final relief in paragraph 112. It seeks provisional measures requiring Myanmar to comply with the Genocide Convention, and final relief finding that it has breached the Genocide Convention.

76. Now it may be that there is a precedent for this, in that these first two requested provisional measures are very similar to the first two provisional measures indicated in the Bosnia Genocide case. But that does not mean that the Court should now follow a 26-year-old precedent given before such developments as the recognition since LaGrand that orders for provisional measures are legally binding.

77. If a Court makes an order — legally binding on a party, and non-compliance with which is a breach of international law — then justice requires that that party be able to know, from the time that the order is made until the time that it ceases to apply, what that party is required to do in order to comply. That is plainly impossible if the content of the obligations imposed by the provisional measures can only be known after the Court has given any judgment on the merits.

78. For instance, in the LaGrand, Breard, Avena and Jadhav cases, the Court indicated provisional measures in terms requiring the respondent State to take all means at its disposal to ensure that named individuals were not executed pending the final decision of the Court. These provisional measures were stated in objective language, with genuine non-prejudice to the merits. But, imagine if those provisional measures had instead stated as follows: “pending a decision on the merits, the respondent is required to take all measures within its power to prevent all acts that constitute a violation of the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations”. What would a respondent State be expected to do?

79. Well, if the Respondent thinks that its conduct does not violate the treaty, it would see no need to change to its conduct. Indeed, its lawyers would no doubt advise it not to cease its conductunless and until a judgment on the merits requires it to do so, since any earlier change in conduct in response to a provisional measures order would be perceived as tacit acceptance that the conduct is in breach of the treaty.

80. On the other hand, the public will undoubtedly perceive the provisional measures as some kind of Court pronouncement on the merits, and the applicant State is unlikely to discourage that. If the Respondent does not change its conduct, the Applicant will now accuse it of breaches of the provisional measures order as well. There will now be two disputes instead of one. Provisional measures orders of this kind will do little to “preserve the respective rights of either party” or to avoid an aggravation of the dispute, which is what they are meant to do.

81. And indeed, there is a further problem. Suppose that the Court were to indicate provisional measures in the terms requested, and were then to find later that it lacks jurisdiction to determine the merits. That would not prevent The Gambia from alleging that the Court still has jurisdiction to determine whether or not Myanmar has violated the provisional measures order. However, to determine compliance with the provisional measures order, the Court would have to determine whether Myanmar had, after the provisional measures were indicated, failed to “prevent . . . acts which amount to or contribute to the crime of genocide”. In other words, in order to determine compliance with the provisional measures order, the Court would need to determine the merits of the case, despite having found that it lacks jurisdiction to do so.

82. Provisional measures in such terms serve no useful purpose. Myanmar, as a party to the Genocide Convention, is bound to comply with its terms in any event, and an order from this Court requiring it to do so does not in any way add to its obligations. But if granted by the Court, politicians, activists and journalists will herald the ruling as a first step in condemnation of the Respondent. For instance, a press release of The Gambia’s representatives, reported in the media, states that the purpose of provisional measures in this case would be “to stop Myanmar’s genocidal conduct immediately”. Also, in oral argument yesterday, Mr. Sands said that the effect of the first and second requested provisional measures is “to prevent the further genocide of the Rohingya group”. Both thereby suggest that a grant of provisional measures would be an acknowledgment that the Applicant’s claim on the merits had already been established.

83. For this reason, judges of the Court have sometimes pointed to the danger of prejudgment of the merits in the award of provisional measures. Indeed, commentators have warned of the danger of requests for provisional measures being made for this very purpose, as part of a political or litigation strategy. It has been said that in some cases the applicant may see the request for provisional measures as more important than the proceedings on the merits, brought in the hope that the Court will make statements that the applicant can use to its advantage before world public opinion even if the Court subsequently finds that it lacks jurisdiction in the main proceedings.

84. Furthermore, and apart from anything else, it is impossible to know what precise conduct might be within provisional measures worded in such broad terms. The Gambia has suggested that these provisional measures might affect, for instance, restrictions on movement in Rakhine State, or the process for applying for national verification cards. How would Myanmar know if, or how, that was so? If there is currently an armed conflict in Rakhine State, will it be suggested that measures taken to deal with this are a breach of these provisional measures if they are indicated?

85. As to the third provisional measure requested in paragraph 132 (c) of the Application, for similar reasons, if Myanmar is to be directed not to destroy evidence, it is required to know what that evidence might be. Of what consists “any evidence related to the events described in the Application”?

86. The fourth provisional measure requested in paragraph 132 (d) of the Application is that “no action [be] taken which may aggravate or extend the existing dispute”. However, any dispute — even if the Court finds there to be one — consists of the sending by one party to the other of a single Note Verbale. It is difficult to see that being aggravated or extended in a way requiring provisional measures. Furthermore, this kind of provisional measure is only indicated in conjunction with other concrete measures.

87. The fifth provisional measure, requested in paragraph 132 (e) of the Application, would require both Myanmar and The Gambia to report to this Court on measures taken. Such a provisional measure would be akin to the reporting obligation under, say, Article 40 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, or Article 19 of the Torture Convention.

However, the Genocide Convention contains no such reporting obligation nor any specific supervisory body, and if it did, this Court would not be the body to which such reports would be submitted. It is not the role of the Court to create human rights monitoring machinery through provisional measures not foreseen in the treaty that allegedly provides for the Court’s jurisdiction.

88. The sixth provisional measure was requested only on 9 December, and would require Myanmar to grant access to and co-operate with United Nations fact-finding bodies that are engaged in investigating alleged genocidal acts. This is not a provisional measure. This is not a measure that would preserve existing rights of the parties pending a final decision by the Court. Myanmar is at present under no obligation under international law to permit access to its territory to, for instance, the Fact-Finding Mission or the Special Rapporteur on Myanmar. Furthermore, even if such an obligation did exist, the basis of any such obligation would not be the Genocide Convention. This provisional measure goes well beyond preservation of any existing rights. It would create entirely new substantive obligations of Myanmar vis-à-vis certain United Nations bodies. Such obligations would have nothing to do with The Gambia, unless The Gambia is contending that such a reporting obligation would be erga omnes. There is no principled basis for this requested provisional measure.

89. Furthermore, this provisional measure would be a circumvention of Myanmar’s reservation to Article VIII of the Genocide Convention, to which I have referred. By virtue of that reservation, other contracting parties may not call upon the United Nations organs to take action under the Charter. The Court cannot impose an obligation which Myanmar has expressly excluded by way of a reservation to which The Gambia has not objected.

90. Mr. President, Members of the Court, that concludes my observations. I would invite you, Mr. President, to call on Ms Okowa to complete the first round of our oral observations.