(The Nation/ANN) —Victor Mallet's guide to the Ganges' many incarnations is to moving that its modern plight becomes all the more tragic

IN “RIVER of Life, River of Death”, Victor Mallet takes the interactions between the Ganges River and the people of India as his focal point in exploring the impact that economic growth has on the environment.

Mallet was the Financial Times’ South Asia bureau chief based in New Delhi from 2012 to 2016, and the newspaper has always kept India high on its agenda. In 2008, Mallet’s predecessor, Edward Luce, examined India’s multitude of contrasts in “In Spite of the Gods”, drawn from his five years as the New Delhi bureau chief.

Mallet, currently the Times’ Asia news editor based in Hong Kong, says in his preface that his principal aim was to tell “at least part of the almost impossibly complicated but exciting story of contemporary India”.

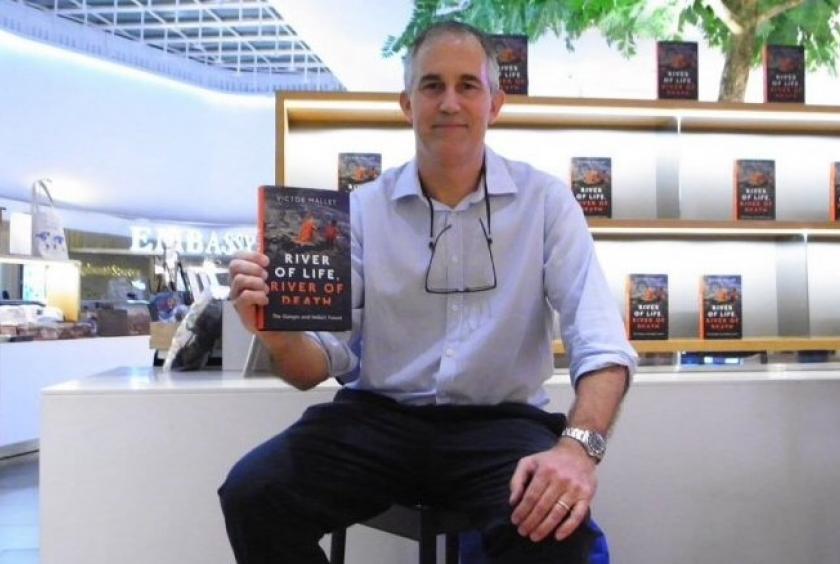

In Bangkok recently to introduce the book at Open House at Central Embassy, he fascinated the audience with tantalising photos from his field trips, including one of the source of the Ganges in a Himalayan glacier. Other images showed the ashrams of Bhujbas and a 19th-century painting of a gharial, the fish-eating crocodile.

This book arrives coinciding with news reports about the degradation of the Ganges, even in the face of India’s ascent in global importance. A 2015 News Week report was headlined “The Ganges is dying under the weight of modern India”. Reuters kicked off 2019 with a lavishly illustrated investigative report titled “The race to save the Ganges”. Both pointed to grim prospects.

Victor Mallet was at Open House in Bangkok recently to talk about his book.

Mallet approaches the subject with an abiding love for the Ganges and the other great rivers of the world. He takes us on a long journey to explore India’s holiest waterway, the religious festivals associated with it and people who depend on it for their livelihoods. As well as its glacial source, we travel to Haridwar, Varanasi, Allahabad and the vast delta where it empties into the ocean.

Mallet should have had a film crew |tagging along. A documentary about his trip to Pinahat, for instance, would surely be great with its population of gharials thriving in the Chambal River, a tributary of the Yamuna, in turn the second-largest tributary of the Ganges.

Assiduously researched, incisively written and carefully argued, “River of Life” reveals how the Ganges has been relentlessly subjected to abuse. These days it looks more like an open sewer, far worse than Bangkok’s San Saeb Canal.

The pollution is a peculiar combination of the effluents of Kanpur, the sewage of Varanasi and the garbage of Patna and Kolkata. Yes, that Varanasi, which lies at the heart of India’s Hindu identity and where many tourists get the best view of the city from a boat on the Ganges.

Some stretches of the Ganges are heavily contaminated with mercury, arsenic, lead and cadmium. An environmental campaigner has described the section in Kanpur as “a toxic cocktail of chemicals”. In Haridwar it was so toxic that in 1984 it burst into flames.

The upper Ganges also remains unsafe, insists Mallet, despite foreign visitors’ |contrary assumptions.

Mallet names the tanneries along the river’s banks in Kanpur and “venal industrialists” as the chief culprits (India is the world’s largest exporter of leather). But ordinary citizens share the blame too.

Hindus including priests in their temples and non-Hindus alike dump just about everything into the river, from plastic bags of garbage and untreated sewage to animal carcasses and partially cremated human bodies.

It’s a terrible shame given that the Ganges is by far the holiest of rivers in Hinduism and that most foreigners who have been to Varanasi, myself included, love all that it represents.

Why the Ganges could be so carelessly abused might have to do with Hindu thinking. They are reluctant to believe that its holy waters can be sullied. It’s postulated that the Ganges descended to earth from the sweat of Vishnu’s toe when he became overexcited watching a young woman dance. In another legend it came rushing from a sacred cow’s mouth. But everyone agrees it is the personification of the goddess Ganga, or Ma Ganga (Mother Ganga).

We are told the government is resolute in its attempt to ameliorate the situation. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has inserted “Ganga Rejuvenation” into the name of the ministry in charge. But, as Mallet acknowledges, India’s environmental laws are lax and inspectors can be bought off for a few thousand rupees.

Nursing the Ganges back to health will be a long slog even if undertaken in earnest, yet, citing the recovery of the Thames, the Rhine and the Chicago rivers, the author appears to be hopeful.

The book is a rich store of anecdotes. The quotations and opinions assembled from a cornucopia of contemporary and historical sources require six pages of bibliography and dozens of pages of notes.

The reader comes face to face with a range of colourful, not-well-known characters like the Aghoris (numbering 1,500 in all of India). They are the extreme sadhus in the fast lane to moksha (liberation) by virtue of their embrace of the “dark path”. Some of them eat the flesh of human corpses while others eat excrement.

Mallet also met one of the few female sadhus – sadhivis – who’d left her daughters behind to pursue her religious goal. But Mallet doesn’t pander to stereotypes.

I found the chapter “Foreigners on the Ganges” particularly engaging. Mallet writes of legendary travellers like Xuanzang, the most renowned of the Chinese pilgrims who went to India during the fifth and seventh centuries, of astronomer Abu Rihan Al-Biruni, who visited from central Asia 400 years later, and of the Moroccan-born Ibn Battuta, who stayed for 14 years.

Battuta recorded in the 14th century that the Sultan of Delhi ordered Ganges water to quench the royal thirst from a locale 40 days distant. Centuries later the emperor Akbar called the same liquid “the water of immortality”.

Xuanzang’s descriptions of the Ganges are likely to stir nostalgia for the idealised rustic Indian landscape, now all but vanished.

“The water is dark blue in colour with great waves rising in it … The water is sweet and fine grains of sand come down with the current … One’s accumulated sins can be expiated by taking a bath in it.”

This book is a thought-provoking read that tries to raise the alarm: the Ganges is dying. Whether Indians want this to happen or not is entirely up to them and their government.